Topic for discussing physics.

Writing Update

(I wrote this for my newsletter.)

I’ve been using a daily writing goal of at least 1000 words for the last several months. This system is more structured than what I’ve used previously and has been working well. I think it’s a good adjustment for a changed situation.

I commonly write between 1000 and 2000 words, sometimes more. I write on weekends too and rarely skip any days. I never count words towards past or future days. Replies don’t count; it has to be a topic I chose myself and wrote about on my own individual initiative. It has to be important – something I think helps make forward progress.

I usually write all the words about one topic. I often write a standalone essay draft. I usually have a few things to say about my topic and finish writing them instead of stopping in the middle.

Writing discussion replies is extra writing, not part of my goal, and I mostly do that after I’ve already finished my writing goal. I generally write in the morning, when fresh, and don’t do much other stuff until I’m done with my main writing for the day. I usually don’t eat until after writing.

I set the 1000 word goal low enough that I can generally do it even if I’m busy for most of the day. It’s just a minimum. The time it takes varies a lot based on how much I’m developing new ideas. And I have flexibility to do other things in the day: read books, podcast, listen to talks, write discussion replies or do non-philosophy. After writing, especially when it went relatively quickly, I try to do at least one more intellectual thing that day. The variety helps avoid burnout. I try to monitor how much I can do without getting too exhausted (getting too exhausted is inefficient). I aim to do near the maximum so that I don’t waste some potential productivity.

Most people can only focus and do good mental work for up to 3 hours a day (the 8 hour workday for knowledge workers or school students is a bad idea). Note that that average includes all days, not just weekdays – you can do a bit more during the week if you take a break on the weekend. I can do more than 3 hours of serious focus per day, but it requires managing what I’m doing, like not trying to write the whole time on most days. I think the 2-3 hour limit is more about methods than anything inherent, and people could increase their limit with skill and knowledge (and that’s why my limit is higher, though still under the 8 hours that many people are supposed to do at knowledge worker jobs).

It helps to have a lot more break time than people get at an office. If you work at home, you can e.g. take a 4 hour break in the middle of your work day. I use non-intellectual activities like showering, eating and exercise as breaks. I intentionally do them in the middle of the day after I’ve already done some writing. If I did them first thing in the morning, I’d be unnecessarily putting two breaks in a row because sleeping already was a break. BTW, naps are the most effective type of break, but I’m often unable to fall asleep during the day because I get enough sleep at night.

I’m currently working on a Critical Fallibilism (epistemology aka philosophy of knowledge) book/website project. I started on this again after finishing my grammar article. I wrote 30,000 words for it last year, and I have over 20,000 new words. Words include notes and outlining, but it’s mostly articles.

The theme I’m working with is error correction. I’m organizing various epistemological ideas around their connection to that theme. I’m also trying to make stuff as clear, practical and approachable as my grammar article. People often read epistemology as abstract stuff for clever discussions, but I want people to actually be able to use it in their lives.

I had planned to write more about liberalism, but I changed my mind. I’m more interested in epistemology. I’m very happy with my article Liberalism: Reason, Peace and Property but less interested (compared to epistemology) in writing followups with more details. The overview article said a lot of what I wanted to write. I do have over 80,000 words written for the liberalism project, mostly from last year. I hope to finish up and share more of it in the future. One particular area I don’t plan to cover in much detail is economics – that’s already covered well by Mises, Hazlitt and Reisman.

I don’t mind writing things which aren’t for a particular project. Having a project goal is useful to help me focus and to help guide me when I’m not sure what to write about. But I also try to be flexible and to follow inspiration when I have it. I also do some freewrites (similar to journaling). If I don’t have an idea for what to write about, sometimes I will freewrite about what I did recently, what my goals are and what I could write about. Another way I find a writing topic is by rereading material, particularly outlines, from my current project. Outlines are like lists of writing topics I can use. When rereading articles, I often think of more ideas to add or think of other issues which aren’t covered.

I’m flexible with my writing goal when doing activities like editing (in which case reducing the word count is often a positive outcome). The real point is to make daily forward progress, not specifically to write new words.

I write more, and edit less, than most writers. I’ve worked to get good at first drafts. When I find out about writing problems, I mainly try to figure out how to not make those errors in the first place rather than how to fix them in editing passes. If you get good at understanding that error, you should need barely any conscious attention to deal with it – you should be able to autopilot dealing with it instead of needing a separate editing pass. (This is the same as how learning in general works.)

I do lots of exploratory writing. I write several articles on the same topic rather than just writing one and doing a bunch of editing. I usually edit after I already have a version that I mostly like. Editing helps polish the details. Writing about cool ideas is generally more fun and educational than editing details, so it’s better to spend a larger proportion of time on that. And there isn’t much point in going through an article and updating everything to fit a major change you just made when you’re still exploring (you may make more major changes and may undo the major change you just made).

People can use editing to reach a local optimum. Sometimes they fix tons of little details, and polish everything, while the big picture is actually wrong. Exploratory writing lets people try out several big pictures and see how well they work. And then the best ideas from each version can be combined.

When editing, people often go in circles because they keep making changes without clearly knowing whether the change is an improvement or not. Editing works better after you’ve already decided what the article should say.

Writing several versions of an article helps you explore what it should say. And it lets you work with largely-independent parts. It splits the overall project up into smaller, more manageable, separate chunks. That lets one deal with less complexity at once which makes things easier and more productive.

For my grammar article, I wrote several earlier versions (and then made major changes which would have been hard to fix in editing, it was easier to just rewrite while referring to the previous writing to reuse the good ideas that would fit into the new version). Plus I broke it into five mostly-independent parts which I wrote on different days. The parts were edited individually, but I also did a couple full-article editing passes near the end. Each part could be thought about and judged on its own, so that limited how much stuff I had to think about at once.

BTW this writing progress update is 1500 words, and I think it’s productive, so I could count it, but I already wrote a 1750 word article today anyway.

I’ve also written 1000 discussion emails and over 700 web posts so far this year. That’s around 10 pieces of writing per day which aren’t included in my writing goal. If you don’t pay attention to my discussion forums, you’re missing out on many ideas.

Related: I like Brandon Sanderson’s writing updates.

What kind of issues do I write about? Check out my Overview of Fallible Ideas Philosophy video or my Fallible Ideas essays.

If you want to support my work, please donate, buy some of my digital, educational products and/or share my work with people. (And thanks a lot to the people already making recurring, monthly contributions totaling more than my rent.)

Are rules your ally or your enemy?

A major political controversy is whether legitimizing misbehavior by a group helps that group or harms that group. Is it good or bad for a group if they can get away with some bad things? Never mind if it's good or bad for other groups. The question is e.g. if you relax criminal law for blacks, does that help or harm blacks (we're not discussing the effect of that policy on whites). If you relax immigration law for Mexicans, are you helping or harming Mexicans? If you relax parental or school rules in response to misbehavior (rather than because there is anything wrong with those particular rules, just to let people get away with misbehavior), does that help or harm children? If you lower the test score requirements for blacks to get into elite universities, does that help or harm blacks?

(Related: Laing legitimized mental illness, while Szasz did not. Szasz always said many people labelled mentally ill are in fact misbehaving, but that misbehavior is not illness. Of course, some people labelled mentally ill were not misbehaving, and misbehavior is often defined by those with power instead of being defined objectively.)

These questions allow for general answers on principle, instead of case by case answers. The political left answers that, in general, the group is helped. I'm speaking here in general terms. Most actual people are pretty inconsistent, but I'm presenting the strong versions of the principled views which inform a lot of actual thinking by that political group.

The different answers come from different views about what rules are. The left views rules as arbitrarily imposed by authority. The rules lack objective value. Rules are obstacles to action. They get in the way. Contradictorily, the left is also in favor of a larger government that makes more rules, as long as they are in power – they want to be authorities who give orders. The left sees the main purpose of rules as to benefit the ruler – they help the people who give the orders, at the expense of those who take the orders. The left's mental model is ruler and ruled, slaver and slave, so they think it's beneficial to the slaves to be exempted from rules (that is protecting them from power and limited the effect of power on their lives).

The right views (proper) rules as objectively helpful (rules which aren't like this are bad and shouldn't exist). Rules help guide people so people know how to behave better. There certainly exist bad and abusive rules (e.g. slavery), but there also exist good and proper rules (objective rules related to the actual requirements of life). The right does want to eliminate bad rules (e.g. many government rules), while the left basically sees all rules as being in one category (arbitrary) and then accepts them. Knowing how to run one's life is hard and moral rules provide guidance. Obeying moral rules makes a person better off. A rule like "don't murder innocents" doesn't just help others (save them from being murdered), it also helps the person who obeys the rule (saves him from being a murderer – being a murderer is actually bad and self-destructive).

Right wing view: relaxing the rules for college admissions lets in unqualified people. Those rules (admissions requirements) were there for a reason. People who don't obey those rules (get good grades, good test scores, etc.) are not prepared for college (at least not the hardest colleges with the strictest entry requirements). Letting them in, when they aren't qualified, is setting them up to fail.

Left wing view: college benefits people and the rules disproportionately keep out poor people, blacks, latinos, etc., so they are being denied benefits. Letting them in will help them get the benefits of a better education and networking with an elite peer group.

Similarly, the right thinks being a CEO is hard and giving someone the job because they are a black lesbian (rather than because they are actually qualified) is setting them up for failure (as well as hurting all the employees and customers). The left thinks being a CEO is a great privilege (it does indeed have big upsides) and so more blacks, females and lesbians ought to receive that privilege. The left thinks the qualifications for CEO are just rationalizations and excuses for bias, while the right thinks objectively helpful criteria and a person ought to want to meet those qualifications, voluntarily, for his own benefit, before he asks to be CEO. Similarly the left thinks men benefit from nepotism while the right thinks they have worse lives. The left's view encourages people to do nepotism (both give and receive) if they can get away with it, while the right claims that is unwise and self-destructive for those involved.

Overall, I broadly agree with the right. Yes some rules are bad, but it's important to understand and voluntarily follow proper rules. Life needs objective guidance, not arbitrary action. There are, in reality, requirements (aka rules) for accomplishing certain goals, gaining certain values, etc.

Note: Understanding the selfish value of moral rules is necessary to understanding the (classical) liberal idea of the harmony of men's interests, including Ayn Rand's pro-selfish moral philosophy. With the left's view of rules, they can't understand such things because they don't even see, on principle, how basic moral advice like "don't be a robber, even if you wouldn't get caught and punished by the police" could possibly be self-interested and beneficial to the person following the rule. Most right-wing, American Christians would have no problem agreeing with that anti-robbing rule, while most left-wing, American atheists would think clearly you'd benefit (by gaining money from the robbery, while having no downside because you aren't caught). I regard the left as encouraging crime and other misbehavior with such views. The left is basically telling people that robbery is great but you can't do it because the police are mean (implication: if you think you can get away with it, go for it. And also you should hate the police and view them as your enemy). The right views the police as allies who only prevent actions they wouldn't want to do anyway, because they don't want to be robbers and they discourage robbery by telling people why robbing is bad for the robber (rather than only bad for the victim).

YouTube and Fair Use

YouTube notified me that they blocked my new video in Japan for copyright reasons. However, confusingly, it's actually blocked in the US while available in Japan. The video is fair use and should not be blocked. (Vimeo and YouTube both have reasonable pages with info saying what is fair use.)

The video is Critical Commentary on "Sucker" by the Jonas Brothers. It educates people on what's wrong with popular culture.

After the video was blocked, I uploaded it to BitChute. That worked but the video quality is low (the lyrics text is blurry). So then I uploaded to Vimeo, which allows higher quality. Vimeo doesn't play ads, but you can't upload much data without paying for an account. Vimeo doesn't have speed controls, so you need to use something like the Video Speed Controller Chrome extension. Vimeo lets you sell videos and associate documents with them, so I could potentially use it as a Gumroad alternative. YouTube has the most users and I'd prefer to use it as long as my videos aren't blocked, although users do need to get ad blocking software in order to have a good experience on YouTube.

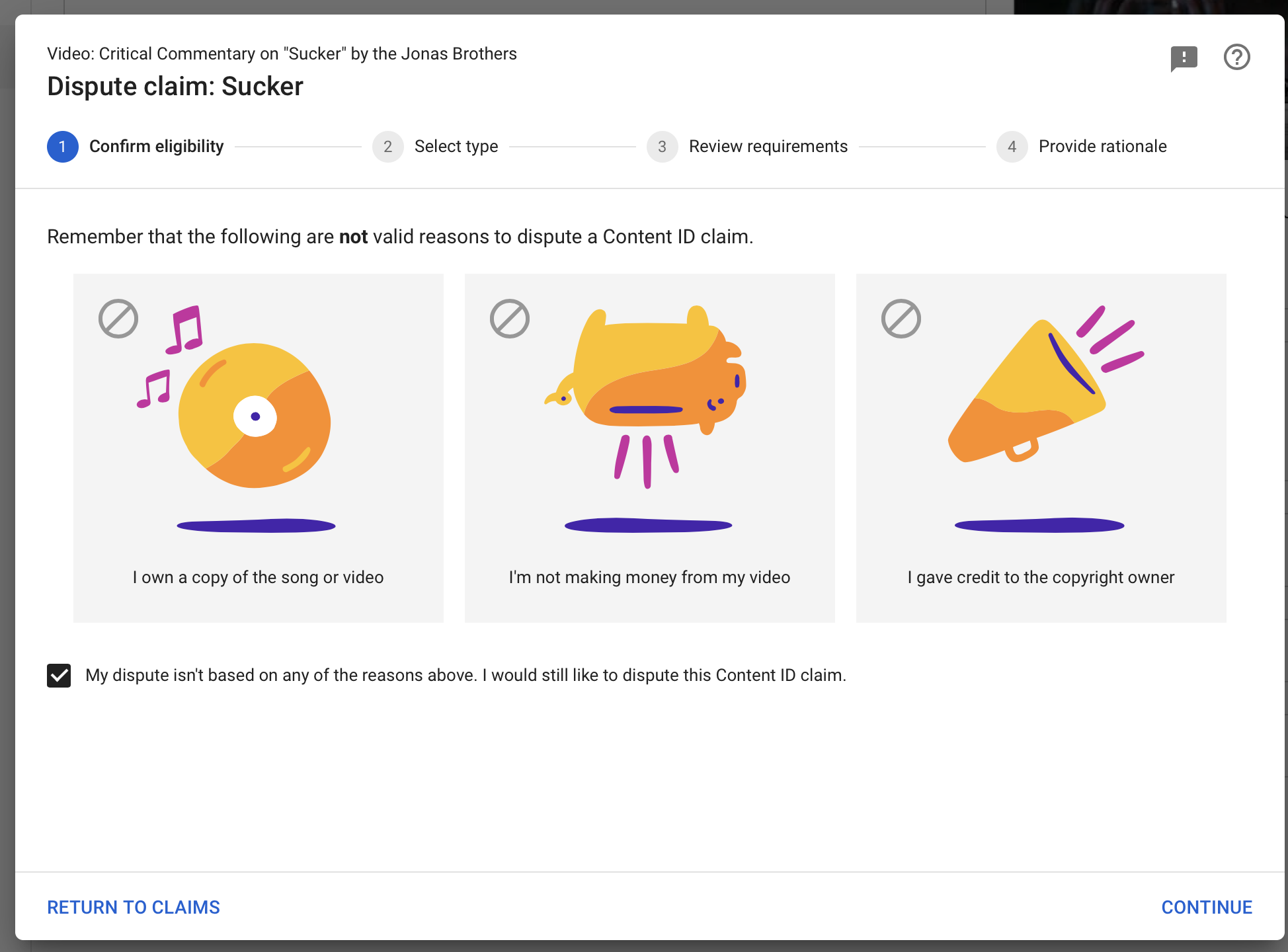

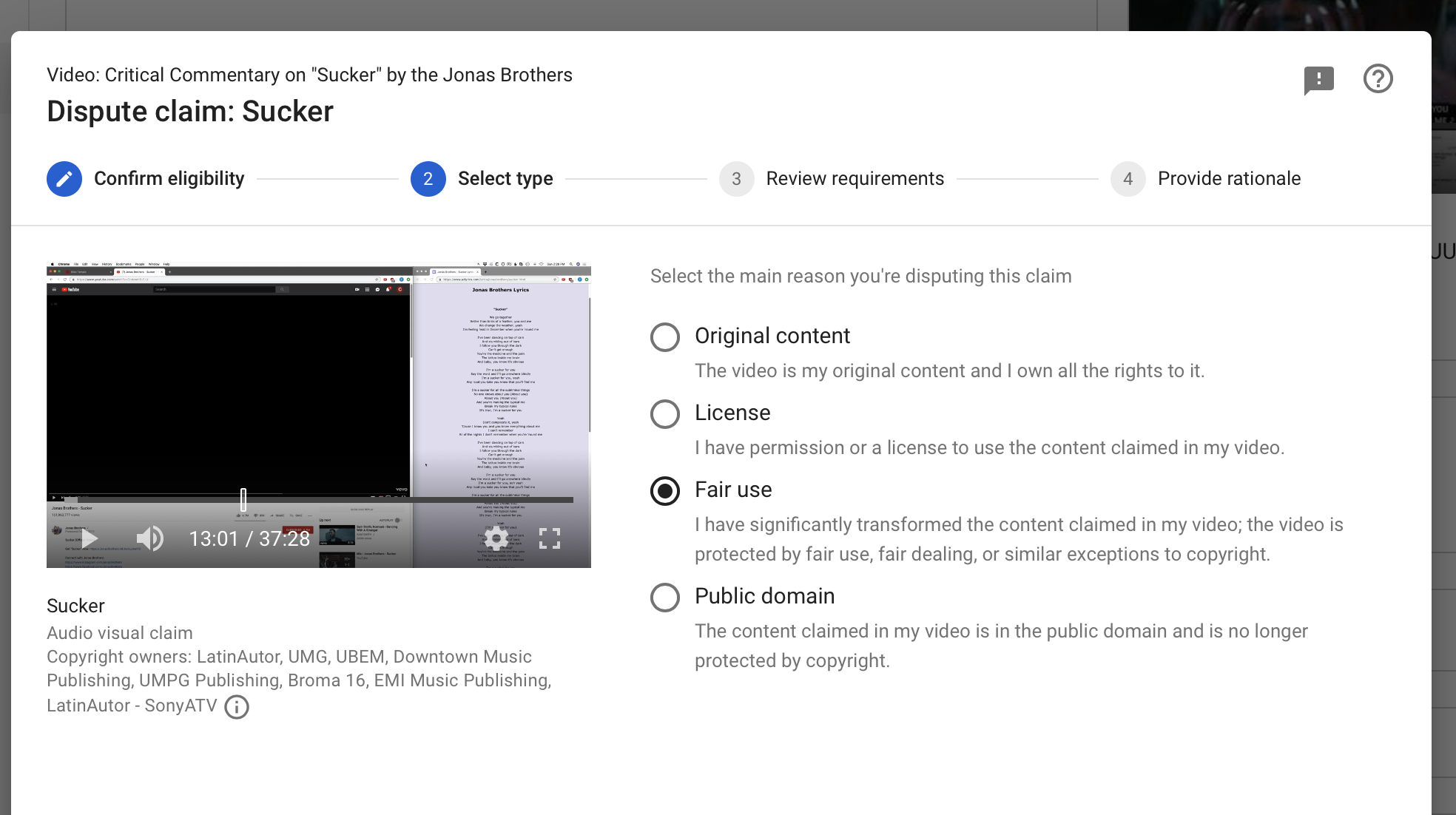

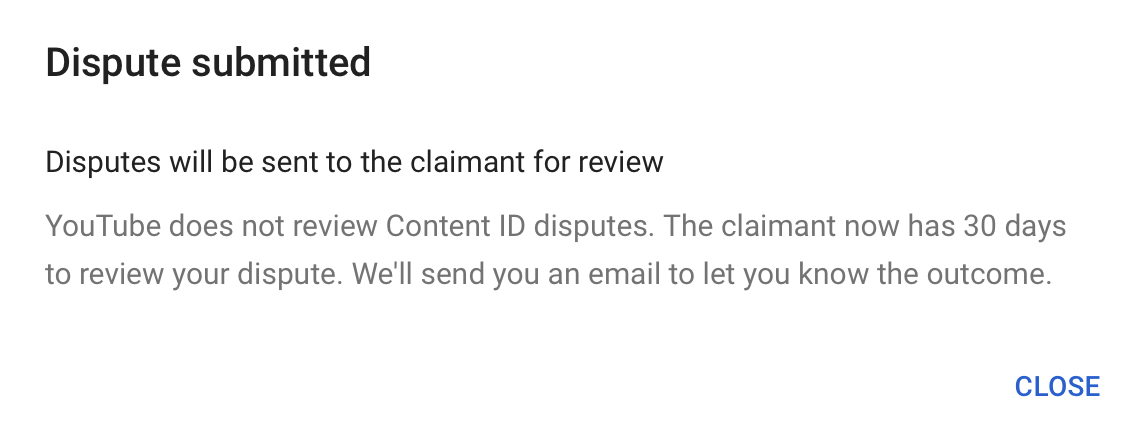

Years ago, I looked at YouTube's copyright dispute process and didn't like it. As I recall, it didn't talk about fair use and it wanted me to provide information so that, if I was mistaken, it'd be easy to sue me. Today, the process is different, so I submitted an appeal. Here's what I wrote (706 characters out of a limit of 2000), then screenshots of the process:

The video is a critical commentary on a Jonas song. It's transformative, educational and non-profit. 90% is just me talking with the song paused. It's a 37 minute video about a 3 minute song. I play a few seconds of the song at a time and then analyze that section. No one would watch my video in place of the original song because I constantly interrupt the music. My video is not musical in nature, so it doesn't substitute for a song. My video is essentially a podcast or lecture which educates people about the flaws in popular culture. Making my video required using the song because the song is the target of my commentary, and the visuals and tone are relevant in addition to the text of the lyrics.

If this works, maybe I'll tell them that my Bones Song Criticism is also fair use. It was only demonetized, not blocked, so people could still watch it, so I didn't do anything. I could also let them know that The State of YouTube Philosophy (+5 video replies) and Teachers Paddling Children are Violent Abusers are fair use.

The video is unblocked while the fair use appeal is pending.

Update: (2019-06-26)

Universal Music Group submitted a second copyright claim on the same video. The first one was apparently just for the visuals, and the second one is for the audio. This time they're trying to block the video in all countries. I disputed the claim using the same explanation that I already used for the first claim. The video is now blocked in all countries for 48 hours (they get 30 days to respond to the dispute, but only 2 days of blocking the video, so they have to respond quickly if they want to keep it blocked).

Alisa Discussion

This is a discussion topic for Alisa Zinov'yevna Rosenbaum (a pseudonym, Ayn Rand's birth name). Other people are welcome to make comments. Alisa has agreed not to post under other names in this topic.

Thinking as a Science by Henry Hazlitt

Henry Hazlitt's Thinking as a Science, from 1916, is short and has good, practical advice about how to think. I particularly recommend chapters 1 (advocating thinking), 5 (about prejudice) and 7 (about reading). The book is free. Go read chapter 1 (11 pages) right now and see what you think. And Anonymous posted some great book quotes.

My comments on a few passages (these are not representative of the book; emphasis added):

The secret of practice is to learn thoroughly one thing at a time.

As already stated, we act according to habit. The only way to break an old habit or to form a new one is to give our whole attention to the process. The new action will soon require less and less attention, until finally we shall do it automatically, without thought—in short, we shall have formed another habit. This accomplished we can turn to still others.

This is something I've been advocating heavily for years. People learn to do something correctly, once, and then think they've learned it and they're done. But that's just the first step. For skills you'll use often, you have to practice until you can do it cheaply, easily and reliably. E.g. I need to be able to type using almost zero conscious attention so that I can focus my attention on the ideas I'm writing. I need to think in an objective – not biased – way pretty much automatically so that I can get on to considering the topic; people who need to use a bunch of mental focus just to avoid bias are handicapped because they have less attention left for the actual topic (and what often happens is, at some point, they focus their attention on the topic and then their habitual bias starts happening).

When I look back into the past, I find nations, sects, philosophers, cherishing beliefs in science, morals, politics, and religion, which we decisively reject. Yet they held them with a faith quite as strong as ours; nay—stronger, if their intolerance of dissent is any criterion.

Intolerance of dissent is not a criterion of strong belief in being correct. It's an indicator of the opposite: lack of confidence in the truth of one's claims. Why suppress dissent when you can win the argument?

If you think a heretic won't convince anyone, you laugh at him and don't care much. If you know the heresy is a threat to your claims, then you try to suppress it.

As William Godwin pointed out, this applies to parenting too. Parents persuade their children with reasoning when they can. Parents resort to using force against their children only when their own rational words fail them.

The practice of Gibbon remains to be considered: “After glancing my eye over the design and order of a new book, I suspended the perusal until I had finished the task of self-examination; till I had revolved in a solitary walk all that I knew or believed, or had thought on the subject of the whole work, or of some particular chapter. I was then qualified to discern how much the author added to my original stock, and I was sometimes satisfied by the agreement, sometimes armed by the opposition of our ideas.”[5]

The trouble with this method is that it is not critical enough; that is, critical in the proper sense. It almost amounts to making sure what your prejudices are, and then taking care to use them as spectacles through which to read. We always do judge a book more or less by our previous prejudices and opinions. We cannot help it. But our justification lies in the manner we have obtained these opinions; whether we have infected them from our environment, or have held them because we wanted them to be true, or have arrived at them from substantial evidence and sound reasoning. If Gibbon had taken a critical attitude toward his former knowledge and opinions to make sure they were correct, and had then applied them to his reading, his course would have been more justifiable and profitable.

In certain subjects, however, Gibbon’s is the only method which can with profit be used. In the study of geography, grammar, a foreign language, or the facts of history, it is well, before reading, simply to review what we already know. Here we cannot be critical because there is really nothing to reason about. Whether George Washington ought to have crossed the Delaware, whether “shall” and “will” ought to be used as they are in English, whether the verb “avoir” ought to be parsed as it is, or whether Hoboken ought to be in New Jersey, are questions which might reasonably be asked, but which would be needless, because for the purposes we would most likely have in mind in reading such facts it would be sufficient to know that these things are so. We might include mathematics among the subjects to be treated in this fashion. Though it is a rational science, there is such unanimity regarding its propositions that the critical attitude is almost a waste of mental energy. In mathematics, to understand is to agree.

The first quoted paragraph is for context. I like the second. But the third is mistaken about math. Mathematicians make plenty of mistakes and have debates and disagreements about what's mistaken. See The Fabric of Reality chapter 10 for arguments on the fallibility of math.

Infinity is an example a contentious mathematical topic. Objectivist philosopher Harry Binswanger denies the existence even of very large integers.

Grammar and history are more controversial topics than math. In my own reading, I've often found rival schools of thought about the interpretation of historical thinkers like Burke or Godwin. The issue arises even for recent history, e.g. there are debates about what Rand's or Popper's personality was like. These debates extend to what certain facts are. Historians debate facts like who wrote a particular book, article or play. They also debate e.g. what information political leaders had at times they made certain decisions, or whether they committed certain crimes or not.

I wrote a recent article on grammar. While researching it, I discovered controversies like whether constituency or dependency is a better way to model grammatical relationships, debates about different ways to interpret words, and even a disagreement about whether verbs are primary in sentences or, alternatively, subject and verb are equally important. And there are a bunch of different lists of standard sentence patterns, most of which are bad because they have a subject+verb+adverb pattern (unlimited adverbs can be added to every pattern, including that one, so it doesn't make sense to have an extra pattern just to include an adverb).

How Discussion Works

The Curiosity website is both a blog and a discussion forum. People have long, serious discussions here (and short or unserious discussions, too).

Every blog post is a discussion topic. There are over 2000. Discuss in any relevant topic, use the generic open discussion topic, or request a new topic. We’re not picky about staying on topic, anyway.

Replying to years-old posts or messages is fine. We don’t have the recency bias found at many forums. Many ideas we discuss have timeless or longterm importance, and continuing old discussions is often better than starting over. The common ways that people find new messages don’t depend on how new the post is.

Discussion Rules

I favor free speech and do not moderate messages. Posting anonymously is allowed and commonplace (you can even have multiple identities and/or change identities). Self-promotion is fine. Off-topic or tangential messages are fine. It’s discouraged to be a jerk or do anything to harm rational discussion (and people may complain or ignore you), but there’s no rule about it. Misquoting is discouraged. If something isn’t an exact, literal quote, you're advised not to use quote marks.

The actual rules are: no doxing, spam, illegal activities or initiation of force. An illegal activity would be posting copyrighted material (quoting parts is fine; that’s fair use). Spam means e.g. an automatic bot that advertises viagra or posts links to websites to try to increase their Google rankings. Doxing includes trying to reveal the identity of an anonymous poster, posting about where people live or work, or posting people’s private characteristics (photos, race, age, who they are dating or married to, etc.). And don’t impersonate other people.

You will never be punished, censored or moderated based on your ideas. You can disagree with whatever you want, advocate whatever you want, and even flame people. The most anyone will do to you is write words back or stop listening. Messages are neutral ground where everyone is equal; there are no special privileges.

Formatting Messages

The title and author fields are optional. Some markdown formatting is supported:

*Italic* and **Bold** are written with asterisks.

Links: A link is automatically created from a URL with whitespace before and after it. You can also do: [link text](url)

Images:

> block quote

>> level 2 block quote (add more > for additional levels)

A level 2 block quote is used to quote a quote. A level 3 block quote is used to quote a quote of a quote. And so on. Contrary to markdown, blockquotes apply until the next newline, not the next double newline.

You can refer to other messages like #1234 and it’ll create a link to the message. Click “reply” at the bottom of a message to auto-generate a reference. Click “quote” at the bottom of a message to get the full text with block quotes added (then just delete the parts you don’t want to reply to).

You cannot edit or delete your messages. If you want to change something, reply to yourself stating the correction. I will try to make message links keep working forever.

You can test/preview comments/formatting by posting in Formatting Test Thread.

New Message Notifications

Find new messages on the recent messages page. For automatic updates, you can use an RSS feed reader (they’re easy) and the Discussion RSS feed (you can add the blog post feed too). RSS readers include Vienna (Mac, free), bazqux (website, $19/yr) and many others. You can also use automatic website change notification software (it’s easy) or an auto-refresh browser plugin.

See also: Use RSS to Subscribe to Blogs

Getting Attention

If I and others don't respond to you, you can try again (saying something similar or something new), ask why, ask what you can do better, or read some of these posts about how to discuss well. Talking about what your goals are, and why you want my attention personally or my community's attention (instead of just wanting discussion with anyone smart), can help. If you think I'm mistaken about something important, see my Debate Policy.

English Language, Analysis & Grammar

Read my new article: English Language, Analysis & Grammar.

Discuss it, and grammar in general, below.

I've also released 14 hours of related video for sale.