Harry Binswanger banned me – an active-minded philosopher who studies and loves Ayn Rand – from his Objectivist discussion forum.

Binswanger is a well known Objectivist. He knew Rand and Leonard Peikoff. He's affiliated with the Ayn Rand Institute and has been involved with some Objectivist books like the second edition of Introduction To Objectivist Epistemology and the Ayn Rand Lexicon. He wrote a book on epistemology, How We Know: Epistemology on an Objectivist Foundation. He published and edited The Objectivist Forum journal. Binswanger now runs an online paid Objectivist discussion forum, The Harry Binswanger Letter (HBL), which he started in 1998.

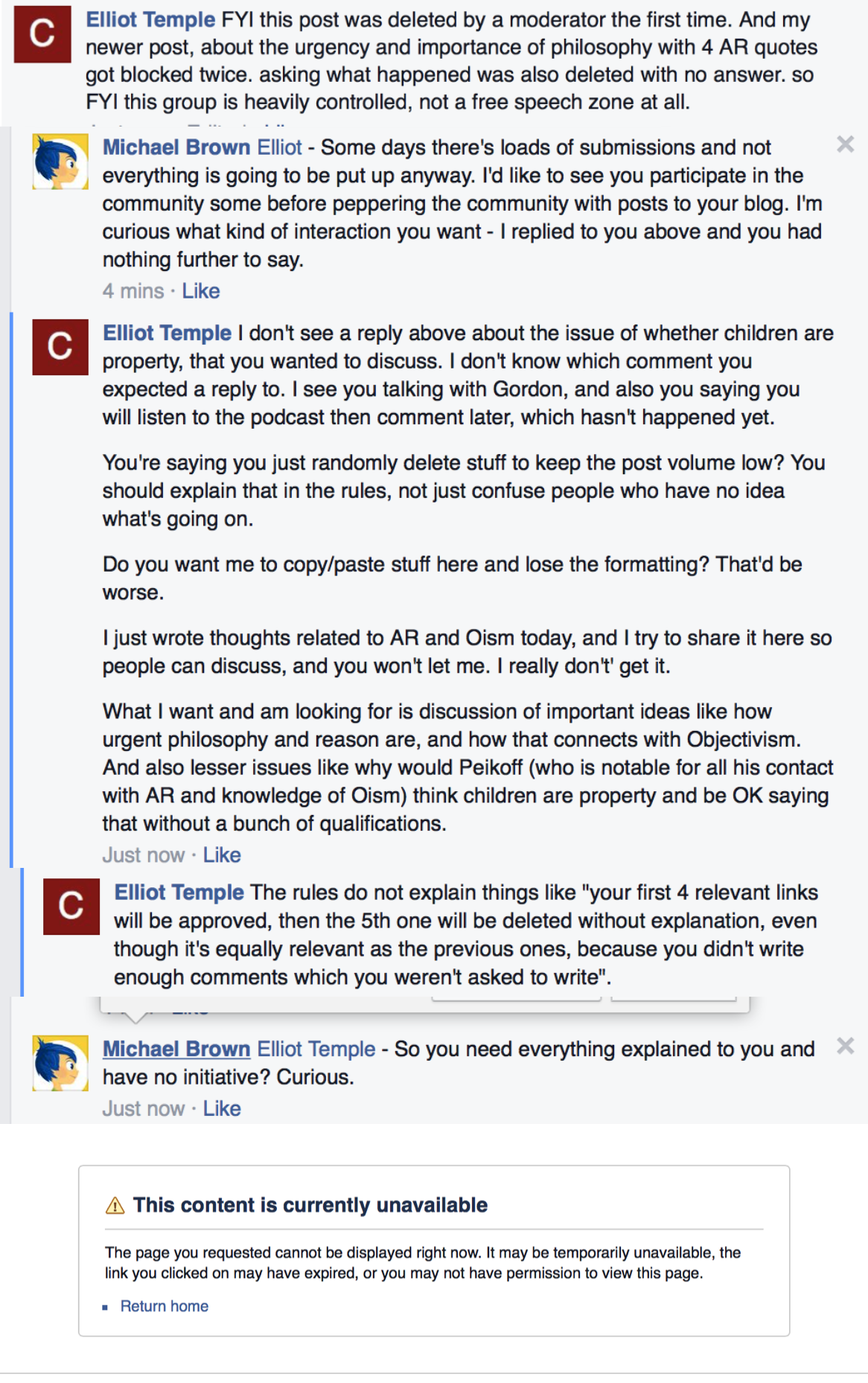

I participated at HBL for the last month. My contributions are publicly available (link).

Binswanger banned me, without warning, because he didn't like my ideas. I wasn't banned for violating any written rule. He didn't try to solve the problem. He hid the problem until the breaking point.

Subjective moderation makes discussion forums bad. Having discussions unpredictably shut down discourages anyone from putting effort into them. (Before banning me he shut down discussions about epistemology, because some readers didn't like them. And he shut down discussion about psychiatry, for no reason given.)

The unwritten HBL moderation policies disallow publicizing any mises.org webpage or George Reisman's Capitalism: A Treatise On Economics, but allow publicizing the evil, anti-capitalist huffingtonpost.com and Paul Krugman.

I advise members to find a better forum.

The announcement banning me, which hides the issue behind the title "Administrative note", reads (bold added, except in the first line):

One-line summary: I have removed Elliot Temple’s posting privileges

After much consideration, I decided to remove Elliot Temple’s posting privileges. His posts were not adding value to HBL, and they were: 1) coming from an alien context, 2) nearly always filled with wrong ideas–sometimes startlingly wrong (your eyes are, he says, “opinionated”)–ideas not well argued for, 3) combative, and 4) skating on the edge of violating our etiquette policy. They also were often too long.

All in all, I began to cringe when I saw his name on a post. Instead of the question “Is anything he’s written actually bad enough to take away his posting privileges?” I realized the question was more, “Why do I want him posting on my list, if almost every post brings me grief?”

After I made the decision, but before he knew of it, he posted a piece charging our dismissal of many of his “criticisms” as evasion–the cardinal sin for Objectivism. But, again, I read that only after reaching my decision.

In private email, he asked me to post the following for him:

1) I’ve been banned from posting to HBL, so don’t expect me to reply anymore.

2) It’s not my choice to end the discussions. I didn’t give up.

3) If anyone wants to continue a discussion, email me ([email protected]). I’m happy to continue any of the discussions and respond to outstanding points, but only if people choose to contact me.

Binswanger considers critics "combative". He cringed each time I'd post a new criticism. He wants passive participants who drop unresolved issues without trying to pursue them to a conclusion. He isn't interested in different perspectives on Ayn Rand's ideas. After thinking about his feelings, he realized he wanted me gone, whether I'd done something wrong or not. He shut down discussion because of his emotional states of cringing and grief.

He says my ideas are wrong. He selected one example to present, but it illustrates his own dishonesty. I said that eyes can see green but not infrared, Binswanger replied accusing me of primacy of consciousness, I clarified again, and Binswanger dropped the topic.

My point, which Binswanger evaded, is that eyes have an opinionated design in the same sense an iPhone camera does. Apple engineers formed opinions about what types of photos are good and designed their camera to produce those photos. They chose lenses according to their judgement of what photos have value to their customers. They run software algorithms to adjust photos to better please their customers. The iPhone doesn't try to show you raw data, it tries to show you (Apple's opinion of) a good photo. (This is not a criticism of Apple's photography opinions, which I consider objectively good. The point is that Apple's judgement is present in the photo you see.)

Biological evolution created a particular range of human eye designs, and not others. Our eyes see some things and not others, and process the data with some algorithms. Our eyes don't just present raw data. They are not the only possible eye designs. These designs were evolutionary selected over others because of their value to the replication of the genes. The human eye is like an opinionated take on which way of seeing has survival value for humans on Earth – like the iPhone camera, it's designed to be particularly good at some things and bad at others, rather than having a neutral design.

I don't know what Binswanger thinks about opinionated camera designs or evolution's design of human eyes. He refused to discuss it.

It's dishonest for Binswanger to use this example to say I was wrong. He took my words out of context to imply I think eyes are conscious (which is ridiculous), rather than fairly presenting my actual views about opinionated designs. And this was the best attack he could come up with to excuse banning dissent.

No one made a complete case that I was mistaken about any idea I presented on HBL. No one pointed out a mistake I made and then argued the point to a conclusion. Nothing got resolved. They did hit-and-run attacks and then didn't address my counter-arguments. Or they'd misunderstand something, then drop the issue when I clarified.

Seeing how our initial discussions weren't reaching resolutions, I started to post about the topic of how to have a discussion. How to resolve debates is a difficult skill worth discussing. I expected discussing our differences to take time, but Binswanger was already out of patience. I talked about how to pursue issues to conclusions. Rather than reply, Binswanger banned me.

HBL is for Objectivists. I'm an Objectivist. I've extensively studied and discussed Objectivism, including over 50 readings of books by Ayn Rand. I agree with Rand more than most, perhaps all, HBL members. I've also studied other Objectivist thinkers, like Peikoff and Binswanger, but I disagree with them more (e.g. regarding induction and their leftwing political sympathies.)

Philosophical Detection

To get into more detail, I'll analyze Ayn Rand's Philosophical Detection, from Philosophy: Who Needs It. I'll compare her views to mine and to Binswanger's. Italics are from Rand, bold is from me.

A detective seeks to discover the truth about a crime. A philosophical detective must seek to determine the truth or falsehood of an abstract system and thus discover whether he is dealing with a great achievement or an intellectual crime.

Ayn Rand (AR) says philosophical detectives "must" figure out what's true and false. That means taking issues to conclusions, not just making a few arguments and stopping before anything is resolved.

The layman’s error, in regard to philosophy, is the tendency to accept consequences while ignoring their causes—to take the end result of a long sequence of thought as the given and to regard it as “self-evident” or as an irreducible primary, while negating its preconditions. ...

As a philosophical detective, you must remember that nothing is self-evident except the material of sensory perception—and that an irreducible primary is a fact which cannot be analyzed (i.e., broken into components) or derived from antecedent facts. You must examine your own convictions and any idea or theory you study, by asking: Is this an irreducible primary—and, if not, what does it depend on?

Binswanger said some of his ideas, like 2+3=5, were unquestionable. He said they were too simple to analyze, criticize, or be mistaken about. He maintained this even after two ways to break 2+3=5 down into components were discussed in detail. (One way involves computer circuits, the other involves Peano Axioms.) Binswanger objected to analyzing the components of arithmetic because he thought consciousness just adds and it's trivial. He treated a long sequence of learning math at school as an irreducible primary.

"2", "+", and "3" are components! Are they too trivial to misunderstand? Binswanger himself makes claims about integers that most people disagree with. Either he's mistaken, or others are, so someone misunderstands integers. Binswanger says infinity is a mistake and even says that very large numbers don't exist, like 10100100.

In modern history, the philosophy of Kant is a systematic rationalization of every major psychological vice. ...

... The wish to perceive “things in themselves” unprocessed by any consciousness, is a rationalization for the wish to escape the effort and responsibility of cognition

Binswanger was consistently hostile to my statements about how we don't perceive things in themselves, and have to actually think to figure out what's in reality. We have to take steps like understanding the physical properties of our eyes, the algorithmic information processing done by our visual system, the physical properties of photons, etc... We have to interpret what we see, taking into account many complex factors. This was the issue he chose to highlight when banning me. AR considers his attitude Kantian.

Perception is one of the areas where Binswanger openly disagrees with AR. He says he disagrees with her in footnote 22 on page 64 of his book How We Know.

Correspondence to reality is the standard of value by which one estimates a theory. If a theory is inapplicable to reality, by what standards can it be estimated as “good”?

This is another area where Binswanger and I disagree. Like AR, I value reality (meaning physical reality!) and I care about how theories correspond to reality. Consequently, I was interested in connecting my claims about epistemology to physics (the science which studies reality). And I spoke about what is and isn't physically possible (possible in reality).

Binswanger didn't care about the project of understanding epistemology in terms of physical reality and physical processes. He was content to treat intelligent consciousness as an irreducible primary without concern for the physical components. And he's a dualist! (That means he thinks consciousness is separate from physical reality.)

Rather than consider topics like evolution and computation which relate epistemology to physical reality, Binswanger treats consciousness as a starting point and believes it has special characteristics unrelated to physical reality. He just wants to do philosophy without worrying about physics too. Why dual major in both like John Galt?

Human brains, being physical objects (and computers in particular), do (physical) information processing. This computation replicates, varies and selects information. It's evolution, literally, and that's how humans are able to learn in physical reality. But Binswanger isn't interested in ideas like these. He'd rather divorce consciousness from the physical world.

The problems Binswanger is trying to address, which drive him to dualism, include dealing with the reality of abstractions and understanding emergent properties. David Deutsch has explained these issues in his books. Binswanger won't read the books which explain better views than he has, nor does he know of any refutation of the books by anyone, nor does he care that the books contain unanswered criticism of his positions.

You must attach clear, specific meanings to words, i.e., be able to identify their referents in reality. This is a precondition, without which neither critical judgment nor thinking of any kind is possible. All philosophical con games count on your using words as vague approximations. You must not take a catch phrase—or any abstract statement—as if it were approximate. Take it literally. Don’t translate it ... Take it straight, for what it does say and mean.

Binswanger repeatedly treated words and explanations approximately. He was unable or unwilling to discuss what Popper and I literally said. His attacks were routinely against unsaid conclusions he jumped to, which we denied. He translated our statements into approximate gists and got confused by narrow, limited statements.

Instead of dismissing the catch phrase, accept it—for a few brief moments. Tell yourself, in effect: “If I were to accept it as true, what would follow?” This is the best way of unmasking any philosophical fraud.

Binswanger used tactics like saying his ideas were unquestionable, and smearing critics as skeptics, rather than carefully and literally considering their arguments. Rather than consider and try to unmask philosophical errors, he spent his time presenting excuses for not thinking about criticism.

Since an emotion is experienced as an immediate primary, but is, in fact, a complex, derivative sum, it permits men to practice one of the ugliest of psychological phenomena: rationalization. Rationalization is a cover-up, a process of providing one’s emotions with a false identity, of giving them spurious explanations and justifications—in order to hide one’s motives, not just from others, but primarily from oneself. The price of rationalizing is the hampering, the distortion and, ultimately, the destruction of one’s cognitive faculty. Rationalization is a process not of perceiving reality, but of attempting to make reality fit one’s emotions.

Binswanger spent more effort rationalizing why not to engage with my ideas than considering my ideas. He felt grief and cringed when I wrote about ideas. He blamed me for his bad feelings. He says he doesn't like my ideas because I'm wrong. He says he dropped out of every discussion because I'm wrong. He came up with rationalizations for his negative emotions about my criticism.

Binswanger didn't win a debate on any point. He dropped out every time. And when I kept talking about ideas, he banned me.

Binswanger didn't make a rational case that I was ruining debate and preventing any conclusion from being reached. He didn't even try. He didn't know of some error I was making that would prevent him from from showing I was mistaken about one point. He just wasn't interested in being challenged. He has a passive mind.

I approached discussion in an active way. When one thing didn't work, I'd try something else. I demonstrated patience and perseverance. For example, I asked people to point out any errors in my methods, but no one had anything to say. And I made a long video where I thought out loud and recorded my writing process. I hoped someone could use the video to point out an error in my approach, but no one did.

I saw Binswanger approach discussion badly in a way which prevented reaching conclusions. He'd make a few arguments, hear a few counter-arguments, and just stop there. He'd refuse to read books. He'd refuse to answer questions. He'd refuse to answer criticisms. He'd misunderstand the same point in the same way, repeatedly, even after multiple clarifications. When I brought this up, I was banned instead of answered. I could have dealt with all those flaws if he'd continued to engage in discussion, but he wouldn't.

I've developed an approach I call Paths Forward for how to take discussions to conclusions. One can always take discussions to conclusions and address all criticism in a timely manner! Isn't that great? Binswanger wasn't interested. He doesn't want to write down his views in public, endorse good writing by others, expose all this to public judgment, and then work to improve his system of ideas to deal with critical challenges. He's content to think he's right, according to his own system of rationalizations, and refuse to deal with mistakes that people point out.

I have an epistemology which gives absolute yes/no answers instead of concluding with the vague maybes that Binswanger favors. Binswanger, like Peikoff, says ideas have a status like possibly, probably or certainly true, rather than dealing decisively with absolutes like true or false. I explained how we can always achieve an up-or-down verdict on an idea in a timely manner. Binswanger wasn't interested.

I say one must address every criticism of one's ideas. I talk about how this can be done without taking up too much time. Binswanger wasn't interested. He felt bad and banned me. What does AR say?

At their first encounter with modern philosophy [like Kant], many people make the mistake of dropping it and running, with the thought: “I know it’s false, but I can’t prove it. I know something’s wrong there, but I can’t waste my time and effort trying to untangle it.” Here is the danger of such a policy: ...

Even if I was advocating Kant (the worst of the worst), AR would say to answer my arguments!

Why bother dealing with criticism? Because you have no way to know which ideas are true or false if you don't. And:

What objectivity and the study of philosophy require is not an “open mind,” but an active mind—a mind able and eagerly willing to examine ideas, but to examine them critically.

Critical discussion is just what I advocated and emphasized, and Binswanger banned me to avoid. I was eager to examine ideas; Binswanger was unwilling.

An active mind does not grant equal status to truth and falsehood; it does not remain floating forever in a stagnant vacuum of neutrality and uncertainty; by assuming the responsibility of judgment, it reaches firm convictions and holds to them.

AR is saying to pursue ideas to the point of actually reaching answers! Don't just stop in the middle! That's what I attempted. Binswanger faked it. He announced some conclusions (I'm wrong!) that he hadn't rationally reached. (What was I wrong about? He declared I was wrong in the middle of the discussion, then didn't allow me to speak further.)

Since it is able to prove its convictions, an active mind achieves an unassailable certainty in confrontations with assailants—a certainty untainted by spots of blind faith, approximation, evasion and fear.

This is what I do and have achieved. I deal with all criticism, and have no fear of it. I have no need to dismiss ideas without answering them because I have answers.

People are welcome to try to assail my ideas. That helps me learn. I've now become familiar with all the common assaults. I learned answers to them or, in some cases, changed my mind.

I wish I could find critics with ideas that would take more effort to answer. Unlike Binswanger, I'd love that. It's one of the things I hoped to find at HBL. I seek out criticism that will require effort for me to address. I seek out challenging ideas.

If you keep an active mind, you will discover (assuming that you started with common-sense rationality) that every challenge you examine will strengthen your convictions, that the conscious, reasoned rejection of false theories will help you to clarify and amplify the true ones, that your ideological enemies will make you invulnerable by providing countless demonstrations of their own impotence.

That's been exactly my experience. But Binswanger banned me rather than deal with a challenge.

No, you will not have to keep your mind eternally open to the task of examining every new variant of the same old falsehoods. You will discover that they are variants or attacks on certain philosophical essentials—and that the entire, gigantic battle of philosophy (and of human history) revolves around the upholding or the destruction of these essentials. You will learn to recognize at a glance a given theory’s stand on these essentials, and to reject the attacks without lengthy consideration—because you will know (and will be able to prove) in what way any given attack, old or new, is made of contradictions and “stolen concepts.”

Of course! If criticisms get repetitive, come up with counter-arguments which address entire categories of criticism at once. Then write them down and reuse them. Learn to recognize when ideas make known errors which already have a written refutation, then give a reference instead of writing something new. This is what I advocate and do, but Binswanger couldn't or wouldn't do it.

Philosophical rationalizations are not always easy to detect. Some of them are so complex that an innocent man may be taken in and paralyzed by intellectual confusion.

I agree. But Binswanger finds it offensive to say you think someone is rationalizing or evading and to explain your reasoning. What's offensive about trying to share useful information about a difficult problem? He doesn't want criticism to tarnish his reputation and he doesn't want to reconsider his ideas.

if the false premises of an influential philosopher are not challenged, generations of his followers—acting as the culture’s subconscious—milk them down to their ultimate consequences.

I challenged Binswanger, who is influential in Objectivist circles, and he banned me for challenging him. One of his excuses was that some of his followers had been complaining. He's attracted followers who don't like challenges, and he tries to please them. (Several people contacted me with positive messages. I think they're too intimidated to tell Binswanger what they think.)

If, in the course of philosophical detection, you find yourself, at times, stopped by the indignantly bewildered question: “How could anyone arrive at such nonsense?”—you will begin to understand it when you discover that evil philosophies are systems of rationalization.

AR's position is like my position, which Binswanger opposed: Rational thinking centers around error correction!

How's it the same? AR says "evil", I say "irrational" and consider irrationality evil. AR says "systems of rationalization", and I know those prevent correcting errors.

AR and I agree: It's the blocking of discussion, the refusal to think about criticism, that's really evil and irrational. That's how people not only arrive at nonsense, but keep believing it over time.

I'd be happy to forgive Binswanger a thousand misconceptions. What ruins him is that he approaches philosophy with an elaborate system for refusing to deal with criticism. He's set things up so that when he's wrong, he stays wrong.

A “closed mind” is usually taken to mean the attitude of a man impervious to ideas, arguments, facts and logic, who clings stubbornly to some mixture of unwarranted assumptions, fashionable catch phrases, tribal prejudices—and emotions. But this is not a “closed” mind, it is a passive one. It is a mind that has dispensed with (or never acquired) the practice of thinking or judging, and feels threatened by any request to consider anything.

Binswanger has a passive mind. Rather than be curious about new ideas, he bans them. Rather than actively consider challenging ideas, Binswanger passively, stubbornly clings to a mix of unwarranted assumptions, catch phrases, prejudices, mistakes – and emotions. Binswanger doesn't pursue ideas to conclusions, so he's missing out on the limitless possibilities of The Beginning of Infinity.

Binswanger Quotes

Here's a brief sample of what Binswanger said on his forum over the last month. (His italics, my bold.)

There's no computation done anywhere outside the human mind. Even computers don't actually compute. In philosophy, we have to speak literally, not metaphorically.

He refused to explain what he means.

I think that it is unquestionable that counting is a simple operation. And it is unquestionable that an adult who adds, with reasonable care, 2 to 3 cannot be mistaken about what the answer is.

(He clarified that he declares it irrational to question the ideas he declares "unquestionable".)

Counting is a physical process which occurs in reality, so how simple it is depends on the laws of physics (and the method used). Physics is not only questionable, it's highly controversial.

it is impossible that I could be mistaken in saying “Two plus three is five.”

The obvious fact is that ... “2 + 3 = 5” cannot be wrong.

That's a tiny sample of his many infallibilist claims. Meanwhile he cast doubt on his own understanding of numbers:

it is widely believed that there’s a number like: 10^100^100. There isn’t.

He also has a problem with infinity.

[The claim that] You can’t guarantee that you reached your decision rationally. [That claim is] false. You can and had damn well better be sure you reached your decision rationally.

He thinks he can't be mistaken about whether his thinking is rational. He claims an infallible guarantee letting him ignore all criticism of his rationality.

Although I hesitate to use terms from an alien context, the closest, of the conventional terms, for the Objectivist semi-position on the mind-brain issue is “property dualism.”

... I’m not sure, myself, whether or not the issue is exclusively scientific.

What I'm resisting is the idea that on the subconscious side there is some unconscious equivalent of computing, judging, deciding. There isn't and couldn't be.

Addition is an action of consciousness.

He thinks the subconscious is like a hard drive that doesn't do any thinking or even compute any algorithms like addition.

Mr. Temple raises the question of how knowledge arises from non-knowledge. It doesn’t.

Also, when you write that you are not “afraid” of the arbitrary, I think you should be. If arbitrary assertions are good until refuted, nothing can be refuted.

positive support comes down to sameness; non-contradiction comes down to difference.

A child pushes a ball and sees it start to move. That is positive support for “Pushing balls makes them move.”

He's a naive inductivist. You look at the world and you see what causes what (somehow).

Now what can epistemology say about the [process of selecting ideas]? Several things, but none that will result in an algorithm, i.e., a mechanically applicable formula replacing judgment.

He presupposes an intelligent consciousness using intelligent judgment as the base of his epistemology. We know by using our intelligent judgment to know! He has no answers to how an intelligent consciousness actually works.

Conclusions

Ayn Rand wrote in The Virtue of Selfishness, How Does One Lead a Rational Life in an Irrational Society?:

One must never fail to pronounce moral judgment.

...

to pronounce moral judgment is an enormous responsibility. To be a judge, one must possess an unimpeachable character; one need not be omniscient or infallible, and it is not an issue of errors of knowledge; one needs an un-breached integrity, that is, the absence of any indulgence in conscious, willful evil. ...

... A judge puts himself on trial every time he pronounces a verdict. ... a man is to be judged by the judgments he pronounces.

...

The moral principle to adopt in this issue, is: “Judge, and be prepared to be judged.”

...

When one pronounces moral judgment, whether in praise or in blame, one must be prepared to answer “Why?” and to prove one’s case—to oneself and to any rational inquirer.

...

Moral values are the motive power of a man’s actions. By pronouncing moral judgment, one protects the clarity of one’s own perception and the rationality of the course one chooses to pursue. ...

Observe how many people evade, rationalize and drive their minds into a state of blind stupor, in dread of discovering that those they deal with—their “loved ones” or friends or business associates or political rulers—are not merely mistaken, but evil. Observe that this dread leads them to sanction, to help and to spread the very evil whose existence they fear to acknowledge.

I judge Harry Binswanger to be immoral. He lacks patience, curiosity, honesty and precision. He wants to tell others what to think and be admired, but doesn't want to learn. He has a system of rationalizations instead of an active mind. He calls his ideas obvious and unquestionable, and claims infallibility, to evade critical debate. He doesn't know how to resolve disagreements, judge ideas, or reach conclusions. He bans dissent that he emotionally dislikes.

If you have questions, criticism, or doubts, write them in the comments below. Don't just tell yourself that I'm mistaken and evade my counter-arguments. Either pursue the issue to a conclusion or don't judge it. And remember that my HBL posts are publicly available to read, so you can fact check my claims.

I'll close with Atlas Shrugged (my bold):

There were people who had listened, but now hurried away, and people who said, "It's horrible!"—"It's not true!"—"How vicious and selfish!"—saying it loudly and guardedly at once, as if wishing that their neighbors would hear them, but hoping that Francisco would not.

"Senor d'Anconia," declared the woman with the earrings, "I don't agree with you!"

"If you can refute a single sentence I uttered, madame, I shall hear it gratefully."

"Oh, I can't answer you. I don't have any answers, my mind doesn't work that way, but I don't feel that you're right, so I know that you're wrong."

"How do you know it?"

"I feel it. I don't go by my head, but by my heart. You might be good at logic, but you're heartless."

"Madame, when we'll see men dying of starvation around us, your heart won't be of any earthly use to save them. And I'm heartless enough to say that when you'll scream, 'But I didn't know it!'—you will not be forgiven."

Update: I've been banned from reading HBL for writing this post (previously I was only banned from posting). Binswanger offered no explanation or reply.